At TouchCare, we often cite the absence of Primary Care Attribution, often associated with preventive care, as an important driver of medical spending for our customers. We took a closer look at some of our own data to prove the correlation between Primary Care Attribution and lower healthcare cost.

In our first part of the series, we discussed what Primary Care Attribution was and why it matters.

Rising Risk Group & PCP Attribution

Rising-risk patients have one or more chronic conditions but are generally stable and do not experience frequent disruptions in their daily life. This segment has higher than average overall healthcare spending but does not utilize significantly more hospital and emergency services than the low-risk group.

Technical definitions of “acuity” segments hinge on claims data. The high-acuity segment represents the 5-15% of the population that drives 50% of total costs. Rising-riskers make up the middle 25-35% of the population and contribute 45% of total costs. The low-risk segment at the bottom of the pyramid represents the 50% of patients who contribute merely 5% of total costs.

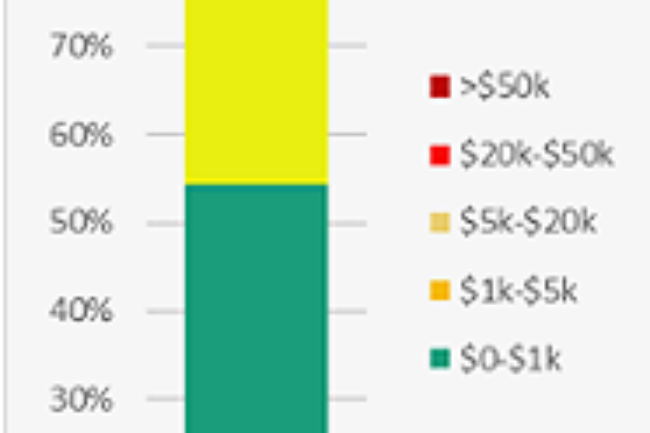

Rising risk can also be defined by the total annual spend. We found the ‘rising risk’ cohort to fit clearly in the $1,000 – $20,000 per year spenders.

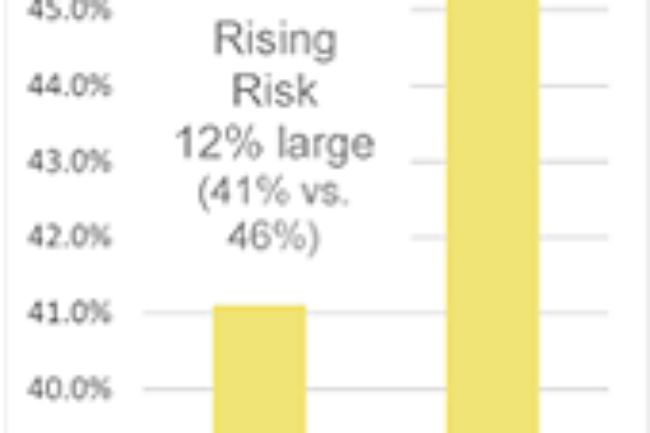

In our study cohort, we found those in the rising risk cohort to be a larger percentage of the members without an attributed PCP vs. those with an attributed PCP. As those members are likely not receiving any sort of preventive care, their conditions are less likely to be proactively managed and more likely to result in high-acuity conditions.

Why and What to Do?

Our anecdotal review of member claims found two possible causes worth exploring.

Many of these patients were under the care of a specialist: endocrinologists, cardiologists, and orthopedic surgeons were the most common. The absence of a primary care physician offering ‘whole person care’ or a comprehensive view may leave this group of patients narrowly treated for one condition when other, latent, conditions exist. This can cause a “whack-a-mole” effect where members are over-utilizing specialists to treat singular conditions, rather than taking a holistic approach to their health & well-being. Additionally, they may not be exposed to alternative treatment plans which may improve their overall health status.

Another possibility may be an undiagnosed condition, in the absence of regular PCP visits, worsened to a point of an acute episode. That acute episode, if not catastrophic, then leads to the member’s rapidly rising medical spend.

Lastly, of course, is over-reliance on the Emergency Room. It’s no surprise that members in the non-PCP group had a higher incidence of using the ER than those with an attributed PCP.

Inhale. We've got this. Exhale.

Understanding healthcare; with us, it’s personal.